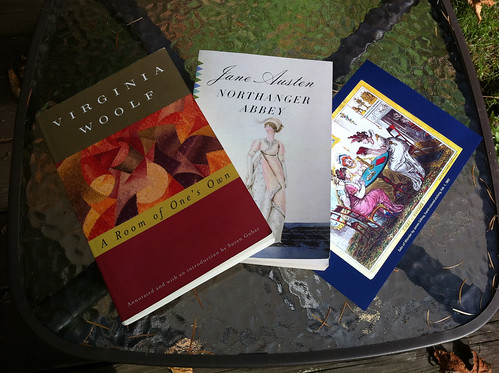

A Room of One’s Own, Northanger Abbey, and a postcard from the Lit Chicks exhibition.

Here was a woman about the year 1800 writing without hate, without bitterness, without fear, without protest, without preaching. That was how Shakespeare wrote, I thought, looking at Antony and Cleopatra; and when people compare Shakespeare and Jane Austen, they may mean that the minds of both had consumed all impediments; and for that reason we do not know Jane Austen and we do not know Shakespeare, and for that reason Jane Austen pervades every word that she wrote, and so does Shakespeare.

-Virginia Woolf, A Room of One’s Own

Whenever anyone mentions Austen and Shakespeare in a breath – and they often do – I think of this section of A Room of One’s Own. Above you see the heart of Woolf’s comparison. Of Shakespeare she earlier writes, “All desire to protest, to preach, to proclaim an injury, to pay off a score, to make the world the witness of some hardship or grievance was fired out of him and consumed.” In Chapter Four, she argues that many female writers’ work is distorted with bitterness and anger at the oppression they have suffered as well as hampered by those obstacles. But Austen, she says, was unharmed as an artist.

It would be easy enough to argue with Woolf’s entire line of reasoning. In modern novels, digressions such as the example she quotes from Jane Eyre, where she decries the restraints on women (“…they need exercise for their faculties and a field for their efforts as much as their brothers do; they suffer from too rigid a restraint, too absolute a stagnation, precisely as men would suffer…”) may not be seen as detracting. One might say that in an age when the model of the artist as genius has retreated, it’s hard to argue that this writer or that writer “got his work expressed completely” as she does of Shakespeare, or that a work which has digressions on the oppression and circumscription of women is growing outside some knowable and natural platonic shape, putting out tumors of misshapen anger. The idea of self-perfected artists putting forth perfect art, however appealing it may be to Austen and Shakespeare devotées like myself, seems a little improbable today.

The Multnomah County Library exhibit I discussed yesterday classed Austen with Shakespeare in the first case of objects, thus bringing this whole line of thinking irresistibly to mind. As I proceeded, I thought about the exception to Woolf’s praise of Austen that I’d recently discovered, and in Case 3 of the exhibition, there was the very quote I had in mind!

You see, I recently reread Northanger Abbey and realized that Austen isn’t entirely “without bitterness” and “without preaching”. Her later books, quite possibly, but in Northanger Abbey, her first completed, she hadn’t yet fired it all out and consumed it. And certainly, she doesn’t express any fiery frustration at the lot of Woman. No, her ire is for the oppressors of the Novel! I will quote at length:

Yes, novels; — for I will not adopt that ungenerous and impolitic custom so common with novel writers, of degrading by their contemptuous censure the very performances, to the number of which they are themselves adding — joining with their greatest enemies in bestowing the harshest epithets on such works, and scarcely ever permitting them to be read by their own heroine, who, if she accidentally take up a novel, is sure to turn over its insipid pages with disgust. Alas! if the heroine of one novel be not patronized by the heroine of another, from whom can she expect protection and regard? I cannot approve of it. Let us leave it to the reviewers to abuse such effusions of fancy at their leisure, and over every new novel to talk in threadbare strains of the trash with which the press now groans. Let us not desert one another; we are an injured body. Although our productions have afforded more extensive and unaffected pleasure than those of any other literary corporation in the world, no species of composition has been so much decried. From pride, ignorance, or fashion, our foes are almost as many as our readers. And while the abilities of the nine-hundredth abridger of the History of England, or of the man who collects and publishes in a volume some dozen lines of Milton, Pope, and Prior, with a paper from the Spectator, and a chapter from Sterne, are eulogized by a thousand pens — there seems almost a general wish of decrying the capacity and undervaluing the labour of the novelist, and of slighting the performances which have only genius, wit, and taste to recommend them. “I am no novel-reader — I seldom look into novels — Do not imagine that I often read novels — It is really very well for a novel.” Such is the common cant. “And what are you reading, Miss — ?” “Oh! It is only a novel!” replies the young lady, while she lays down her book with affected indifference, or momentary shame. “It is only Cecilia, or Camilla, or Belinda”; or, in short, only some work in which the greatest powers of the mind are displayed, in which the most thorough knowledge of human nature, the happiest delineation of its varieties, the liveliest effusions of wit and humour, are conveyed to the world in the best-chosen language. Now, had the same young lady been engaged with a volume of the Spectator, instead of such a work, how proudly would she have produced the book, and told its name; though the chances must be against her being occupied by any part of that voluminous publication, of which either the matter or manner would not disgust a young person of taste: the substance of its papers so often consisting in the statement of improbable circumstances, unnatural characters, and topics of conversation, which no longer concern any one living; and their language, too, frequently so coarse as to give no very favorable idea of the age that could endure it.

-Jane Austen, Northanger Abbey

[emphasis mine, to show the approximate quote used in the Library’s exhibition]

Here is a digression indeed! And every bit as long, I judge, as the passage in Jane Eyre Virginia Woolf disapproves (though Austen has placed it at the end of a chapter, thus escaping the “awkward break” whereby Woolf declares Brontë’s “continuity is disturbed.”)

Now perhaps even the scrupulous Woolf would pardon Austen’s vigorous asides in defense of the novel, since they come throughout Northanger Abbey and the perusal of novels does figure quite prominently in the plot, albeit not in the a uniformly positive light. But it seems that Austen was not entirely unscratched by the hardness of the world, and did pick a fight or two. Of course, by standing up for the respectability and literary worth of the novel, she was joining a battle in which she could make a difference: one you could fairly say that she won.

I digress still further – and perhaps engage in preaching and bitterness? – in the stunning conclusion to “Only a novel!”. Stay tuned!

Comments

An earlier room

Tangentially related: I discovered just yesterday that Harriet Beecher Stowe wrote “If I am to write, I must have a room to myself, which shall be my own” prior to Woolf, according to Joan D. Hedrick’s biography of Stowe.

Re: An earlier room

Interesting, but perhaps not unexpected, since both came from (by modern standards) large families — Woolf especially so. In the context of Austen, it’s interesting to note (as Woolf does) that she didn’t have a room of her own. She quotes Austen’s nephew: “How she was able to effect all this is surprising, for she had no separate study to repair to, and most of the work must have been done in the general sitting-room, subject to all kinds of casual interruptions.”